|

The Inside Story

Where have our Historic Interiors Gone?

By David Marshall, AIA

Prado Restaurant: The old Cafe del Rey Moro restaurant in Balboa Park was built in 1935 and restored in 1997. This view shows the restored dining room prior to the Prado Restaurant moving in. The majority of historic features, including the spectacular stenciled ceiling, was saved and can still be seen today.

|

Palace Cafe: This terrific dining room, once on the ground floor of the Plaza Building in downtown San Diego, is now only a memory. Note the Baroque ornamentation, mosaic tile floor, ceiling murals, and handsome chandeliers.

|

House of Hospitality Office: This historic interior from 1935 is relatively modest, but was saved and restored because it displayed important historic characteristcs of the building. Note the faux stone mantle, "schoolhouse" lights, and custom-replicated curtains.

|

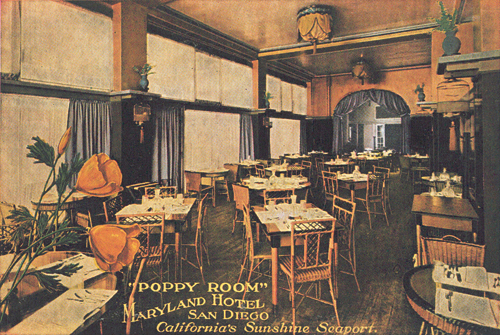

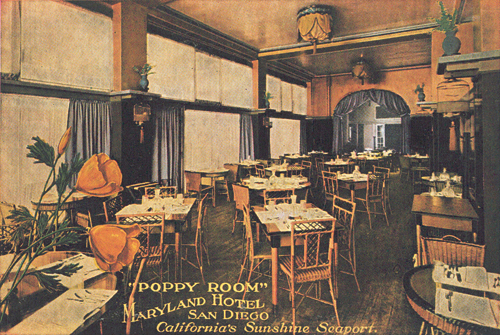

Maryland Hotel: This postcard image shows the hotel's Poppy Room with its unique light fixtures, trim, and window coverings. This is one of the historic interiors that was unceremoniously demolished by prior and current ownership.

|

U.S. Grant Hotel: Despite its recent rehabilitation, much of what can be seen in this postcard of the U.S. Grant's lobby has been lost since 1910. The plush seating, ornate chandeliers, and historic color scheme have all been replaced.

|

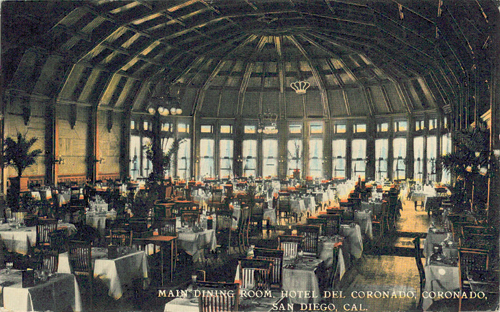

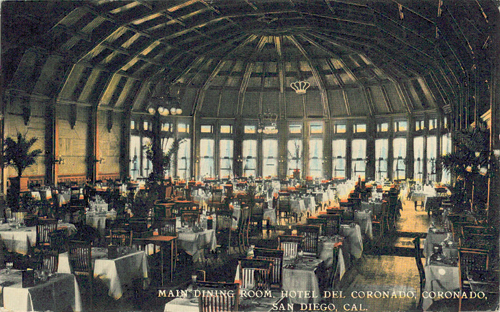

Crown Room: The famed dining room of the Hotel del Coronado was constructed in 1888. Thankfully, this one-of-a-kind interior has been spared from Navajo White paint, chic updates, and other remodeling disasters.

|

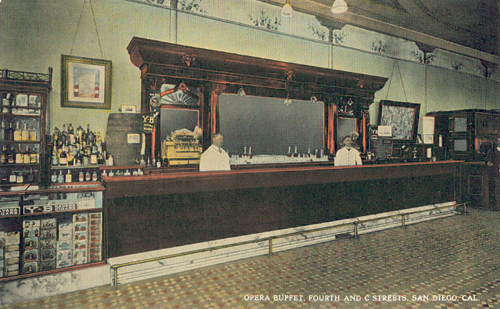

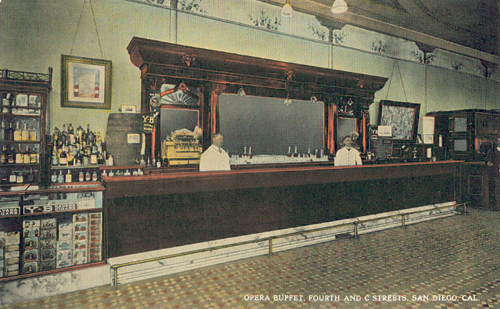

Opera Buffet: This traditional bar was once located in downtown San Diego. Several new bars in the Gaslamp Quarter have attempted to recreate this look and ambience, but they can never be the real McCoy.

|

Carlsbad Mineral Springs Hotel: This ornate lobby, constructed in 1930, included colorful Spanish Revival stenciling, terracotta tile, a flagstone fireplace, and wall murals depicting California's missions. The hotel once played host to stars Greta Garbo, John Barrymore, and Bing Crosby. In the 1950s and 60s all of the walls and ceilings were obliterated with white paint. The destruction of the once-grand interior helped justify the complete demolition of the hotel in 1990s.

|

How many of us have walked into a historic building and suddenly felt lost? Where is the original woodwork? What happened to the light fixtures? Why is there a vinyl floor? What happened to the history? This is what I refer to as Vacuous Building Syndrome. It's the condition where the outside of a building looks historic, but the inside is soulless and devoid of a past.

This is a preservation dilemma that is occurring with increasing frequency. Building owners, developers, and tenants are tearing out historic interiors at an alarming rate. Every day, dumpsters are being filled with mosaic tile, hand-troweled plaster, bronze hardware, marble countertops, tin ceilings, douglas fir cabinetry, ornate light fixtures, panel doors, and maple floors. Like Halloween pumpkins, the insides of historic buildings are being scooped out and thrown in the trash without a second thought.

Why is This Happening?

There are three main reasons why historic interiors get destroyed: 1) ignorance, 2) ego, and 3) laziness.

Ignorance is a root cause because owners and designers often don't understand that interiors of historic buildings have value - aesthetic, financial, and cultural value. Owners and designers don't realize that intact interiors are even more rare and valuable than intact exteriors of older buildings. The truth is that destroying interior features actually decreases the value of a historic structure, both now and for future owners. Tearing out a historic interior is the epitome of ignorance.

Ego is not rare among architects, developers, business owners, or interior designers. In our disposable, fashion-conscious world, ego often trumps history. An old interior is something that someone else did, and the egocentric must replace it with a design of their own creation. Rather than sharing the stage, old with new, many designers want a clean slate, requiring erasure of a building's rich history. The most creative designers aren't afraid of incorporating the creativity and craftsmanship of prior generations into a completed project. Enlightened and skilled designers understand that it is the mix of old and new that adds life and interest to any older building.

Laziness comes into play when the people who decide to tear out the old do so because it is seen as the path of least resistance. They'd rather start with a faceless, colorless void that they can shape without worrying about harmony or context. Often times the interiors they perpetuate are not unique or custom-designed, but are generic fashion statements that are repeated verbatim by other "cutting-edge" designers in Los Angeles, Miami, or Phoenix.

Hitting Home (Like a Sledgehammer)

In San Diego, recent "upgrades" to two historically designated hotels have resulted in the complete loss of intact historic interiors. Instead of recognizing the benefits of historic interiors, the developers and their misguided designers transformed positive attributes into a negative black hole.

The Keating Building on 5th Avenue and F Street in the Gaslamp Quarter has been home to Croce's Restaurant for many years. The Keating Building was constructed in 1890 as a first-class office building and is listed on the National Register of Historic Places. It is one of the most handsome and recognized buildings downtown. The Keating also happened to have one of the finest intact 19th century interiors in San Diego, complete with wood panel doors, transom windows, and original 1890s finishes. The interior had character and charm and was a perfect fit for the Gaslamp Quarter. Not anymore.

The Keating was recently converted from offices into a trendy "ultra-chic" 38-room boutique hotel on the upper floors. The remodel resulted is the destruction of historic interiors that had been carefully preserved and restored for more than 115 years. The hotel's designers decided to save nothing that they didn't have to, so they gutted it to bare studs and designed a brand new interior without a hint of the building's past. History was wiped clean. Today the Keating Building is no more than an empty shell, gussied up with a trendy facelift that will be passé in three years.

The other butchered historic hotel is the 1915 Maryland, now named the Ivy Hotel, on F Street between 6th and 7th. The new owners decided to scrape the grand old hotel back to the studs in the mistaken belief that there was nothing on the inside worth saving. There is no reason why a building that was built as a hotel must be gutted to create yet another hotel. Hallways, stairs, and doors are already there and can be modified to accommodate any new layout. I'll never forget the sight of a demolition worker driving a mini bulldozer through the first floor of the Maryland, its front blade tearing up hundreds of square feet of 90-year old mosaic tile flooring.

The Ivy Hotel's website blathers: "Contemporary luxury envelops and whispers elegance. Peek behind the classic and refined façade to reveal mischief and sensuality underneath. Be whoever you want to be. Your secret is safe at Ivy. Let inhibitions slide to the floor as you expose every one of your senses and indulge completely."Won't the hotel's guests be surprised when they find that once they are inside the $350-plus per night "historic" hotel there isn't so much as a toothpick of historic interior remaining. Chic leather-clad columns and a minimalist front desk now dominate the Ivy's pretentious lobby. Why would a guest bother to stay in a 90-year old hotel if the goal is to avoid anything historic? Imagine if the operators of the Hotel del Coronado had followed the Ivy's misguided design philosophy.

Both of these recently mutilated hotels are not just quaint old buildings, but are designated historic structures. One would like to ask a simple question of the people responsible: "If you loathe historic buildings so much then why did you put your business in one?"

Who's in Charge Here?

Unfortunately, the ordinances in place to protect historic buildings are often limited to protecting only their exteriors. Many owners and designers only preserve what they are forced to preserve. The result is unfettered ravaging of historic interiors.

When one reads the "bible" of historic preservation, the Secretary of the Interior's Standards, interiors are supposed to receive the same treatments and protections as exteriors. They are considered equally valuable and worth saving.

But since the purview of the San Diego Historical Resources Board (HRB) is limited to the protection of exterior "publicly visible" facades of designated structures, historic interiors have virtually no local protection unless they are separately listed in the designation paperwork. This has been a rarely utilized protection.Even the Mill's Act, a statewide property tax reduction program for historic buildings, has no control over changes to the interior. What about the Gaslamp Quarter, one of the city's most cherished collections of historic structures? There is no protection for historic interiors in the Gaslamp Quarter Design Guidelines either.

In contrast to local regulations, the California Office of Historic Preservation (OHP) has stringent oversight of interior alterations for Federal Tax Incentive projects and California State Parks is very strict regarding interior alterations to the historic buildings that they oversee.

What Can Be Done?

The San Diego Historical Resources Board has formed an "Interiors Ad Hoc Subcommittee" to establish a process to evaluate and designate important publicly visible interiors. Current city codes allow for designating interiors, they just haven't being utilized. The subcommittee will be recommending the following:

- Interiors should be considered for designation based upon public visibility and access. For example, even a "private" building like a hotel has publicly accessible interior spaces like a lobby, ballroom, corridors, etc. which should be evaluated for designation.

- Public buildings must have their interior spaces evaluated in the standard research reports that are required for the HRB designation process.

- Single-family residential interiors would usually be exempt from non-voluntary designation. But there could be occasions where the HRB would recommend designation of a residential or private interior space if it were especially rare or significant.

- The HRB needs to focus on education about proper treatments to historic interiors and promote their value to property owners, tenants, and designers.

Clearly, the status quo of not designating the interiors of historic buildings must end if we are to save them for future generations. Historic buildings commonly go through hundreds of owners and tenants over their life spans. It only takes one to erase that history forever.

Historical significance doesn't stop at the threshold.

Author David Marshall is a San Diego architect who specializes in historic preservation and adaptive reuse. He is a member of the Historical Resources Board and is a former president of SOHO. |

MORE FROM THIS ISSUE

The Broadway Fountain

San Diego's Historic Warehouse District

Just the Facts

National City & Otay Railroad Depot

The Inside Story

2007 Most Endangered List

Sim Bruce Richards

2007 People In Preservation Award Winners

Baseball Returns Downtown

Reflections

Lost San Diego

Strength in Numbers

Advertisements

DOWNLOAD full magazine as pdf (24mb)

|