BETWEEN THE YEARS 1841 and 1869, the United States witnessed one of the greatest migrations in its history.

For nearly three decades, settlers emigrating from the eastern United States were spurred by various motives, among them religious persecution, homesteading opportunities, and economic incentives. But it was the 1849 Gold Rush that brought the largest waves of people. The history of the overland trails and the emigrants who traveled them are some of the most significant influences that shaped the nation.

There were other routes west but most people traveled on overland trails. It took a typical emigrant family three to six months to make this roughly 2000-mile journey.

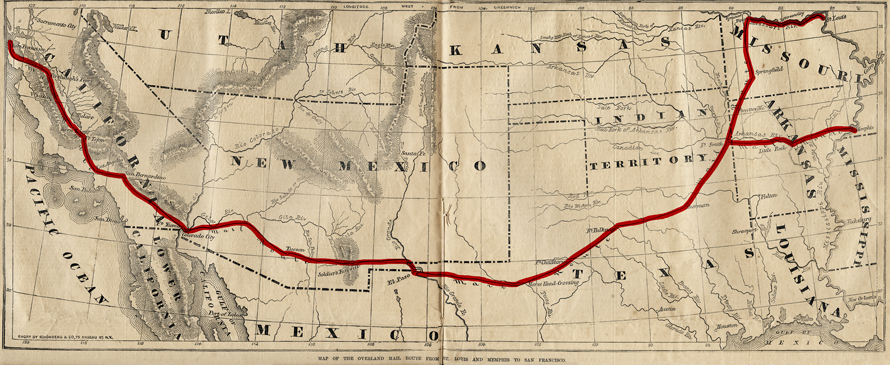

The Southern Emigrant Trail, was also known as the Gila Trail, Kearny Trail, Southern Trail, and Butterfield Stage Trail. It was a major land route for immigration into California from the eastern United States.

Unlike the more northern routes, travel was possible year-round as mountain passes were not blocked by snow. However, the Southern Emigrant Trail had the disadvantage of intense summer heat and lack of water in New Mexico's desert region's (which included what is now Arizona), and the Colorado Desert.

These trails began as animal paths worn further by indigenous peoples, fur trappers, and mountain men, and finally, as overland passage for the general American public.

During the years these overland trails were in use, settlers' relations with Native Americans changed. Indeed, at the start of their journey, they represented the greatest fear for many emigrants. After some time on the trail, most learned that there was little reason to be afraid. Instead of fighting, most natives wanted to trade with the travelers for useful things like metal pots, beads, ammunition, and cloth. The emigrants often needed things indigenous people had to offer, too, like robes made from animal skins, fresh food, and help in crossing rivers.

As its popularity increased and emigrants began settling along the trail, relations between groups became strained. Emigrants consumed resources, contaminated water supplies, and transmitted diseases. In the end it was Native Americans who had more reason to fear the emigrants. Within 50 years of the first wagon trails, Whites had disrupted or nearly destroyed their traditional ways of life. |