|

La Neighbor: The Heart and Soul of a Community

March/April 2017

By Bobbie Bagel

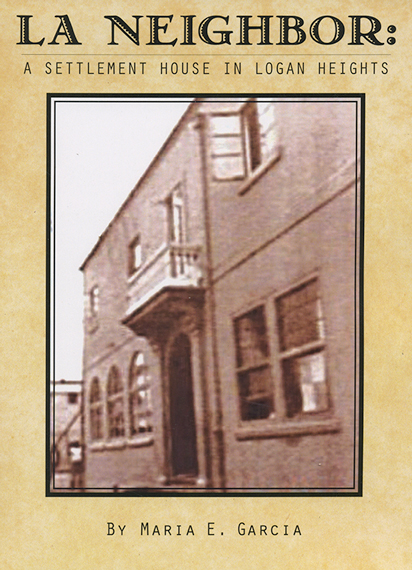

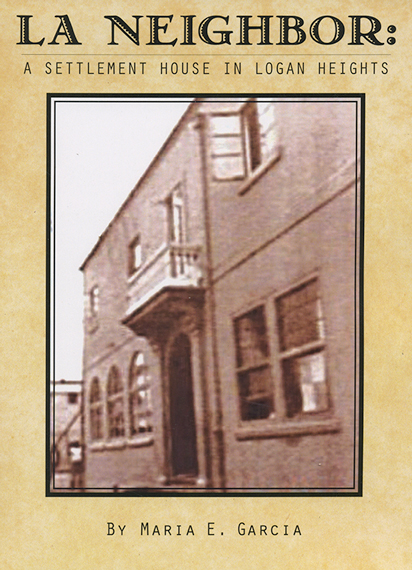

La Neighbor: A Settlement House in Logan Heights

327 pages, $30

Signed copies are available at the Marston House Museum Shop, 3525 Seventh Avenue, San Diego 92103 |

|

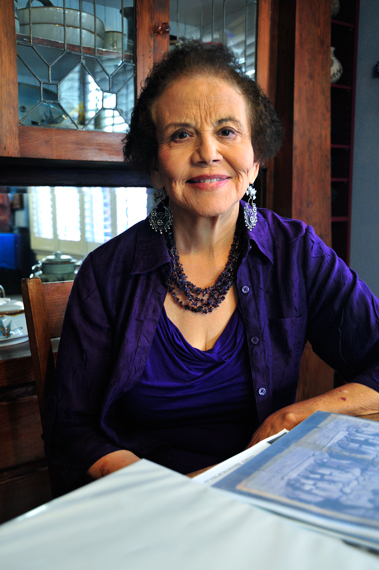

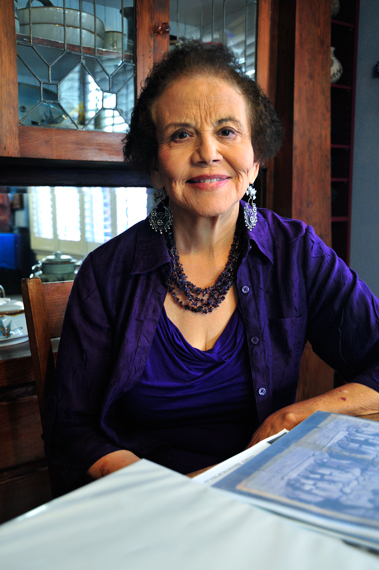

Preservation is not only about buildings, it is also very much about community. Author Maria Garcia, who received a SOHO People in Preservation Award in 2015, has produced a remarkable book. It chronicles how one building in Logan Heights-the Neighborhood House at 1809 National Avenue-became the heart and soul of the Mexican immigrant community for more than seven decades.

Garcia's book includes her own essays and dozens of oral histories (recuerdos/memories) from neighborhood residents, both past and present. There are over 130 photographs of the people who lived in this bayside community, just southeast of downtown San Diego. More than 100 reproductions of newspaper clippings, hand-written letters, and documents provide valuable insight into the life and times of Logan Heights.

A retired school principal and Chicana activist, Garcia begins her account around 1914 when Neighborhood House was just getting started. (La Neighbor means Big Neighbor, Garcia writes.) It was patterned after others founded through the settlement house movement in major cities across the country. Settlement houses were organized to aid refugees escaping violence, poverty, and the ravages of war in Europe. The goal was to help them assimilate into American life. Progressive activists, predominantly well-educated women, like Jane Addams and Eleanor Roosevelt, led the effort.

At the same time, here in San Diego, there was a large influx of immigrants fleeing the chaos of the Mexican Revolution. Helen Marston was a progressive young women inspired to help the poor families crossing the border. Having previously trained with Jane Addams, Marston was the driving force behind Neighborhood House in Logan Heights.

In fact, the entire George Marston family was dedicated to the project. Garcia sites many examples. Mary Marston, Helen's older sister, chaired the Board of Directors. The Marston home on Seventh Avenue was the site for elegant fundraising garden parties. Since Marston's Department Store was a major advertiser in the local newspapers, Neighborhood House activities always received excellent coverage. And when a blind, ailing father from the community was dying, he asked Mary Marston to take in his orphaned daughters. One of those young girls was Laura Rodriguez. She lived with the Marston family for several years and then went on to become a courageous Logan Heights leader.

When the Great Depression hit, Neighborhood House mobilized. With an annual operating budget of roughly $10,000, the staff tried to help everyone they could. Since few local homes had ovens, an outdoor brick oven was constructed behind the building. Joe Serrano, who attended kindergarten at Neighborhood House, recalled that it was there that he tasted bread for the first time. Fruit trucks dropped off fresh watermelon, peaches, and oranges. Tuna fishermen occasionally came by to offer part of their catch.

Various civic groups sponsored all types of activities at Neighborhood House including citizenship classes, English classes, summer camp, and a training program for household maids. Tulie Trejo learned to bake at Neighborhood House. She went on to win the Pillsbury Bake-Off three times! Flamenco was very popular in the dancing classes, and the Singing Mothers of Neighborhood House, performing in traditional Mexican attire, were in great demand.

Health concerns were crucial. Neighborhood House offered nursing classes, immunizations, and a pre-natal and well-baby clinic. The House kitchen doubled as a surgery; Emma Arroya Lopez remembers having her tonsils removed there. In 1936, a British colleague of Margaret Sanger spoke on the benefits of birth control, a daring topic at the time. Many residents who had no running hot water at home came for hot showers.

Coach Merlin Pinkerton organized team sports at the House for thirty years starting in 1940, including wrestling, boxing, baseball, and even tennis. He became a mentor and role model for the boys, helping them find part-time jobs, and getting them out of minor scrapes with the authorities.

While Garcia presents a portrait of a generous, close-knit community devoted to Neighborhood House, she also exposes the pervasive discrimination residents faced. During the Depression, the San Diego Board of Supervisors banned Mexican immigrants from getting jobs in Works Progress Administration projects. The WPA was a federal lifeline for the unemployed. At the same time, mass deportations were taking place. The population of Logan Heights dwindled. Nationally, more than two million people of Mexican descent were forcibly repatriated.

From the start of the Second World War and for the next twenty years, Logan Heights was a place of turbulent change. A huge influx of sailors arrived at the 32nd Street Naval Station and a USO center opened behind Neighborhood House. Local businesses thrived. Meanwhile, young local men were enlisting and being drafted in large numbers. Better-paying jobs opened up for both men and women in the defense plants that now choked the bay front.

The 1960s ushered in a very different kind of war: the War on Poverty. The comforting, effective communal approach of Neighborhood House was tossed out, replaced by rigid, bureaucratic institutional methods. The lively settlement house was turned into sterile administrative offices.

At the same time, the community was literally torn apart. The construction of Interstate 5 cut a wide, cruel slice through the center of the neighborhood, demolishing homes, displacing families, and disrupting everyday life. It split Barrio Logan from Logan Heights. Another stunning blow came a few years later. In 1967, construction began on the Coronado Bay Bridge and its enormous pylons were anchored in neighborhood land. By the time the bridge was completed in 1969, residents had had enough. Influenced by the civil rights and anti-Vietnam war movements, Chicano activists found their voice.

The community had been promised a public park below the bridge. In the spring of 1970, when bulldozers began construction on a Highway Patrol Station instead of a park, residents organized and took action. Laura Rodriquez was one of the first to lie down in front of the bulldozers. A standoff ensued. Twelve days later, Logan Heights activists had won. Chicano Park was born. Community artists and Chicano artists from other cities painted the now famous murals on the massive cement pylons. And in January, the park was designated a National Historic Landmark, the highest honor for National Register sites.

Laura Rodriquez led the way again in October 1970. This time, she chained herself to the doors of Neighborhood House. Activists were demanding the House once again serve as a medical clinic. They won that battle, too.

Take a ride through Logan Heights. Drive by the corner of National Avenue and Beardsley Street (named for Helen Marston Beardsley). The Neighborhood House building at 1890 National Avenue is gone, replaced by a large, impressive, modern structure: the full-service Logan Heights Family Health Center. Continue on a few blocks to Chicano Park, under the bridge at 1949 Logan Avenue. Look for the mural that portrays the proud, determined face of Laura Rodriguez beaming down, keeping watch on the neighborhood she loved.

|

2024

2023

2022

2021

2020

2019

2018

2017

2016

2015

|